I am not a scientist; I am not a philosopher; I am not a theologian; and I am not a politician. I could make a long list of the things that I am not. What I have spent almost 40 years trying to become is a generalist who focuses on finding commonalities between diverse bodies of specialized knowledge. Beginning with college, I have spent almost all of my adult life pursuing an integrated worldview, or paradigm, which makes sense of the complicated, chaotic, and ever-changing world in which we live. The good news is that I believe I have found what I was seeking. It is a global paradigm that is evolving naturally all over the world in virtually every major discipline of study, not only in scientific circles but also in more subjective areas that influence religious and political thought.

This blog is about that emerging worldview. A blend of systems thinking and an evolutionary perspective, it is built around three unchanging principles of change that have governed the evolution of everything – from the universe, to life, to our personalities and cultures, to our technologies and economies. It is also built around ideas of how these three basic principles continually balance against each other in an unending tug-of-war. When the balance is just right, the cacophony of competing interests that so characterizes modern life becomes a beautiful symphony of cooperation and wholeness. My goal in writing this blog is to share with others what I’ve discovered so that they can better understand and adapt to the tidal wave of revolutionary changes that seem to be confronting us nearly every day.

The ideas in this blog are entirely my own, but having said that, I owe a debt of gratitude to a number of people who have helped me along the way. In this first blog entry, I want to particularly acknowledge one person who had a major influence on my thinking – A. Earl Swift, an entrepreneur and philanthropist who was a philosopher at heart. His ideas on basic principles of organization helped shape the ideas I will present in this blog, and I think a quick summary of his ideas (at least from my point of view) will provide a good way of introducing the three principles of change that I will be discussing from this point forward.

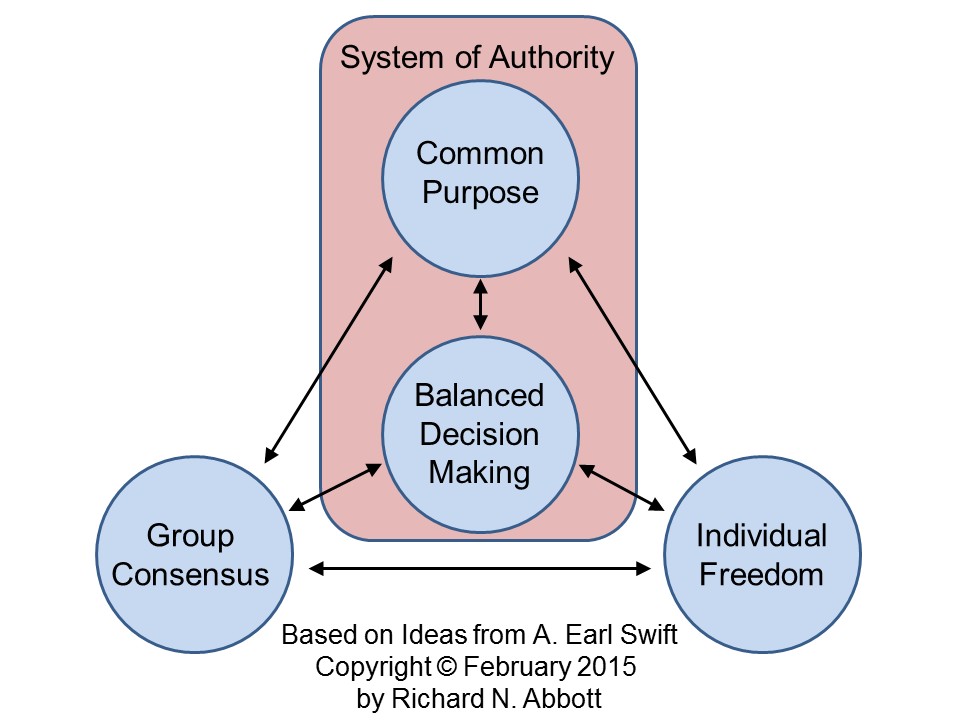

Earl was the founder and chairman of an independent oil and gas company listed on the New York Stock Exchange. I began working with him in 1988, an association that ended with his death in 2006. Very early in our conversations, he introduced me to what he believed were the three primary types of organizational decision making: [1]

- individual decision making based upon self interest;

- group decision making, based upon some kind of consensus; and

- authoritative decision making based upon purpose-centered hierarchies, rules, or values.

The system of authority within any organization was defined by its overall purpose and by its balance of the three ways of making a decision (see diagram below). Earl believed that these three types of decision making corresponded to three basic human drives:

- the need to be free to follow our own desires,

- the need to belong to a community of like-minded people, and

- the need to achieve meaningful common goals.

Said differently, we all desire individual freedom, community belonging, and meaningful purpose in our lives.

In one of his papers on how effective leaders further these principles in their organizations, Earl put it this way[2]

“I have spent a lot of time trying to understand human nature, and I have become convinced of these truths: In interpersonal relationships, people are always striving to be free, to belong, and to achieve. Leaders help others accomplish their individual goals. They help others become part of a team. Most importantly, leaders help others reach beyond themselves to accomplish some greater purpose.”

I have this quote framed with his photo in my office. It was his philosophy of leadership in one short paragraph.

For Earl, these three ways of making decisions and their corresponding drives also constituted three ethical systems that complement and balance against each other as we make our day-to-day choices. Having built a company from a two-person office into a large, publicly held corporation, he had seen first-hand how these three systems of ethical principles interacted with each other in a variety of organizational contexts.

Three Ethical Systems. The first ethical system is based upon individual freedom. We are driven to pursue our individual desires and dreams. But in order to achieve those goals, we require the help of other people (often more than we realize), and so we have to take the needs of others into account. To succeed in a free system, we have to forge win-win bargains with those around us and treat other people as we would want to be treated ourselves. Earl was a master at creating win-win relationships, as many entrepreneurs are. He called it aligning the interests of the parties.[3]

He knew that the ethics of individual freedom is the ethics of reciprocity.[4] [5] [6] We are free to pursue our own dreams – provided that we help other people achieve their dreams as well. It may not seem obvious, but true freedom only occurs in a group setting.

It’s easy to underestimate how much groups shape our individuality. One of the main ways we become unique is by taking on specialized roles, but specialization can only exist within groups. If we were all on our own, each one of us would have to do everything, and we would all be pretty much alike. Earl once made this point by saying: [7]

“Evolution has built into us the drive to freely express ourselves as individuals because it serves as the primary source of specialized abilities, and specialization gives group activities much of their survival value. We join together in groups because others can do things for us that we cannot do for ourselves. “

Of course, freedom not only facilitates specialization, it also produces variation and diversity. Variation and diversity form the ultimate source of innovation and adaptability, which together fuel the engines of progress. Over the long term, freedom is an essential component of group productivity. We all benefit when everyone is free.

Unfortunately, when we forget this lesson, individualism can get out of balance. People sometimes abandon win-win solutions and use their personal or institutional power to force others to cooperate against their will. But pure power-based relationships are the antithesis of freedom, and they usually don’t lead to sustainable progress. We are never truly free and we will never be truly secure and prosperous until we respect the freedom of our neighbors.

The second ethical system is based upon group consensus, founded on our innate need to belong to communities of like-minded people. In this ethical system, accepted social norms are passed on to us from respected role models. A key word here is “accepted.” What we think depends in part on what other people think, and the more people that think a certain way, the more pressure we have to adopt that same kind of thinking.

This second ethical system is designed to promote cooperation within close-knit social bands, such as the family, and serves to define who’s a member of the group in good standing and who’s not. It promotes compromise and conformity, tends to treat all members of the group as equally important, and exalts in team loyalty and shared efforts. In this system, we tend to favor those who have characteristics similar to our own, and the more similar they are to us, the stronger the bond we share. In helping others within the group, we help ourselves because we further individuals who are like us. Earl once put it this way: [8]

“You help the other guy because he is like you. In helping him, you are helping yourself, increasing the probability that your genes (or perhaps your culture and your values) will continue after you are gone. “

This is the foundation of kinship-based cooperation. We love and nurture the people in our family because they are like us in many ways. They are part of us. We share the same genes. We share the same life experiences. We share common values. Cooperation within the family is ultimately based upon commonality. So is cooperation within other social organizations.

When this ethical system gets out of balance, it results in unfair discrimination against those who are not part of the “in” group. It can also lead to a kind of “group-think” where the risks of a decision or the benefits of alternative choices are not adequately considered.

From the point of view of society, consensus-based decision making provides the social cohesion necessary for us to live and work together in groups. Without a minimal level of compromise and consensus, civilization would be impossible.

The final ethical system is the ethics of purpose-centered values and ideals, based on our inborn need for a sense of meaningful common purpose and ideological integrity. This ethical system seeks to achieve common goals, respects visionary leadership, and identifies with principled decision making. It is ultimately founded on either religious faith or secular ideology. We do what we think is right because it gives us a sense of integrity and wholeness, and because it fills our life with meaning and purpose. When this system gets out of balance, we become inflexible and intolerant of people whose ideals and goals differ from our own.

Earl saw a lack of balance in this third ethical system as one of the major problems of our times. We live in an increasingly global economy without an integrated set of shared ideals that would allow globalization to flourish. On September 11, 2001, in the aftermath of the attacks in New York and Washington, he took me aside and told me he wanted to write a book on this subject, and we started to labor on his manuscript together. Sadly, he did not live to accomplish his goal. We are left with several of his published papers and with the unfinished manuscript that gave us some tantalizing clues to his broader thinking.

Three Types of Transactions. Some of that broader thinking had to do with interpersonal transactions. When we interact with each other within organizations, we engage in a mixture of three basic types of transactions – economic, social, and ideological – based upon the three ethical systems described above.

In economic transactions, it is the value of goods or services being exchanged that dominates the interaction. The relationship of the parties to the transaction is often irrelevant. We will buy goods from strangers provided we can be reasonably sure that the exchange will be fair and equitable.

When you buy a new phone at a phone store, you don’t know the people who built the phone. You may know the brand, which tells you something about the reputation of the manufacturer and perhaps the cell phone carrier, but you probably never previously met the salesperson who is talking to you across the counter. In fact, you aren’t that interested in the lives of the people involved. What you care about is the quality and reliability of the phone and the service that comes with it. If the quality is good, not only are you and your salesperson satisfied, you both feel better off afterward than you did before. You now have the latest in communication technology, and the salesperson is happy to have made a sale. Individual needs have been met through a reciprocal exchange – a win-win transaction.

Economic transactions are based primarily upon reciprocity even when they don’t involve money. One form they take is the exchange of favors. The professional network LinkedIn is a good example. I will link to you if you will link to me. Or perhaps I watch my neighbors’ house when they are out of town, if they will watch my house when I am gone. We help others because we expect them to help us in return. Fairness and justice prevail in these transactions when the relative value of what we exchange is approximately equal.

Another important requirement for economic exchanges is that they provide synergies. As in the example at the phone store, economic interactions occur voluntarily because both parties believe they will be better off as a result of the trade. The whole is equal to more than the sum of its parts: the transaction must be win-win for a voluntary exchange to occur. As I will discuss in later blog postings, this implies that free economic transactions are only sustainable in an environment of economic growth. Only with ever-increasing value are repeated win-win transactions (where both parties are better off) sustainable over a long period of time.

Unlike economic exchanges, social transactions don’t focus on a reciprocal exchange of benefits. It is the relationship of the parties, rather than the things being exchanged, that dominates the interaction. [9] A mother bakes a cake for her one-year-old or a father builds a tree house for his children with no expectation of payment in any form: the relationship between the parent and child is what matters. We cooperate with others in order to build relationships with them or to assist those who are important to us. We seek to understand the other people involved, and we often empathize with their emotions and feelings. We usually have an emotional investment in these relationships, valuing them in their own right rather than just for the reciprocal benefits we might derive from them. We may also have strong emotional ties to what we learn from those relationships. As Earl once said: [10]

“For better or worse, we have strong feelings about many of our social transactions. They are deeply wired into our psyche and tied to some of our strongest drives. We learn most of our social rules from our parents when we are still young, and our emotional attachment to those rules helps cement our social bonds.”

While it is easy to see that most family activities involve social transactions, these social interactions are also the ethics behind many business relationships. We may mentor a young person who reminds us of ourselves, or we may exhibit loyalty to our team. As in the case of the family, it is the relationship of the parties that defines the nature of the interaction.

In ideological transactions, we do what we think is right because it furthers principles or values that we hold dear. It is the principles behind the transaction that dominate the interaction. We do the right thing even when there is no reciprocity and even when we don’t have much in common with the other person. We may follow charismatic leaders, even if they are strangers, because we identify with their vision and values; or we obey instructions from our superiors because we believe in the legitimacy of their authority, even if we don’t agree with the proposed course of action and even when its not in our own self interest.

A volunteer at a church, or a person who donates to the victims of a recent disaster, or an unpaid worker in a political campaign might be carrying out an ideological transaction. When a transaction is based upon ideological principles, we promote an idealized vision of the future that resonates within our own souls and within the hearts and minds of those around us. In a very real sense, this inner harmony is its own reward. Some studies with very young children suggest that this principle-centered altruism may have its foundation in natural altruistic tendencies that are found early in child development, and these innate predispositions are shaped by later socialization [11] into true ideological and moral values – “love your neighbor as yourself,” for example. [12] Of course, these kinds of principle-centered values can also have a dark side – ” an eye for and eye and a tooth for a tooth” comes to mind. [13]

Beyond helping others, the universal principles undergirding ideological transactions serve another very important purpose. They integrate the various roles we play into a cohesive whole. An effective set of integrated principles reaps a great practical benefit in that it aligns our activities in a common direction, focusing our efforts on a single vision of a better future. We are more likely to be successful if we are not working at cross purposes with ourselves. The probability of success increases even further if the activities of an entire group can be focused on achieving the same set of common goals. Universal principles therefore become an integrating ideal, both for the individual and for the group. They serve as a unifying vision of right and wrong – a basic sense of what is worth pursuing in life. They provide the basic mechanism for evaluating all of our goals, giving each of those goals its ultimate meaning. Aristotle called these unifying principles the target “at which all things aim,” meaning that all our goals and objectives must be evaluated in the light of what we hold as our ultimate purpose – what we believe to be our ultimate reason for being.

It follows that effective organizational leadership must promote goals that are consistent with these integrating ideals. Leadership must be principle centered. It must be founded on a meaningful vision of the future that resonates with the values of both the leadership group and the people being led. But that unity of purpose cannot be achieved without taking the whole person and the whole organization into account. Effective goals must be built upon a balance of our inner drives for individual freedom, group belonging, and meaningful common purpose. Only then can organizational goals find the harmonious resonance with our inner nature that leads to successful performance.

Achieving Balance. In an individual, this balance is achieved through the choices we each make. Our choices shape our character and our character shapes our choices through an ongoing feedback loop. People of good character exhibit a balance between the three primary drives for freedom, community, and purpose. They are not inordinately selfish, focusing exclusively on meeting their own personal needs, but neither are they people pleasers, focusing excessively on what other people want and expect. They also cannot be too ideological, or they will become inflexible, insensitive, or overly judgmental of others.

In the same way, successful organizations of every kind exhibit a healthy culture designed to achieve balanced decision making. Some decisions are decentralized and flexible in order to allow an appropriate amount of individual initiative and creativity, as well as to provide a chance for people to develop themselves professionally and fulfill their own personal ambitions. Other decisions are based upon social consensus in order to preserve and enhance the network of relationships upon which teamwork and cooperation are based. Still other decisions are guided by the organization’s leadership as they set forth the vision and core principles that guide organizational behavior.

Organizations with healthy cultures shun the same pitfalls that individuals with good character avoid. They cannot become too individualistic, otherwise anarchy and chaos will reign supreme; neither can they become too consensus oriented, lest they succumb to inflexible groupthink or unreasoning prejudice; they also cannot become too goal oriented, lest they become tyrannical in their tone and rigidly mechanical in their operation. Successful organizations, just like successful individuals, exhibit a balance between the three primary human drives.

The balance within an organization is determined by the organization’s system of authority. For individuals, that system of internal authority is our free will guided by internal character and values. We balance the three drives by making decisions, and our inner sense of “I” makes those decisions based upon the values and principles we consider most important. Our cumulative choices are an expression of our innermost spiritual self, and the ability to choose is at the center of who we are. As author Stephen Covey said in his book The 8th Habit: [14]

“If you were to ask me what one subject, one theme, one point, seemed to have the greatest impact on people – what one great idea resonated deeper in the soul than any other – if you were to ask what one ideal was most practical, most relevant, most timely, regardless of circumstances, I would answer quickly, without any reservation, and with the deepest conviction of my heart and soul, that we are free to choose. Next to life itself, the power to choose is your greatest gift.”

The power to choose is also the essence of organizational authority. In fact, a textbook definition of authority is the “power to determine, adjudicate, or otherwise settle issues or disputes.”[15] In an organization, authority determines how decisions will be made.

In the United States government, that primary system of authority is generally considered to be the U.S. constitution. The constitution apportions power among three branches of government representing the three primary human drives. The courts determine individual rights and responsibilities; the legislature deliberates and enacts legislation in pursuit of social norms and group consensus; and the president provides purpose-driven leadership. By apportioning power among the three branches, the constitution sets out the process through which decisions will be made and balance will be achieved.

But mere words on parchment would have no practical effect if the constitution did not reflect the shared values that the people of the United States had agreed to accept as guiding principles. This becomes abundantly clear during times when those constitutional ideals are put to the test.

Consider the landmark Supreme Court decision Oliver L. Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka Kansas [16] that outlawed racial segregation in schools, a case that is often placed on a short list of the most important Supreme Court decisions in U.S. history. Chief Justice Earl Warren felt it was important for the Court to render a unanimous decision in that case because he realized that the Court’s authority rested in some degree on its unified moral voice. The Court had no power to enforce the decision on its own. It required assistance from the executive branch of government and from the states, and Chief Justice Warren knew that the needed assistance would be obtained as much through moral influence as through authoritative command.

The same is true for any form of organizational authority. No decision can be effectively implemented without the voluntary cooperation of others. Shared values therefore become the most basic expression of authority, serving as the guide for each individual’s daily choices. Only shared values are flexible enough and pervasive enough to provide guidance through the thousands of collective decisions made on a typical day in every organization of any significant size.

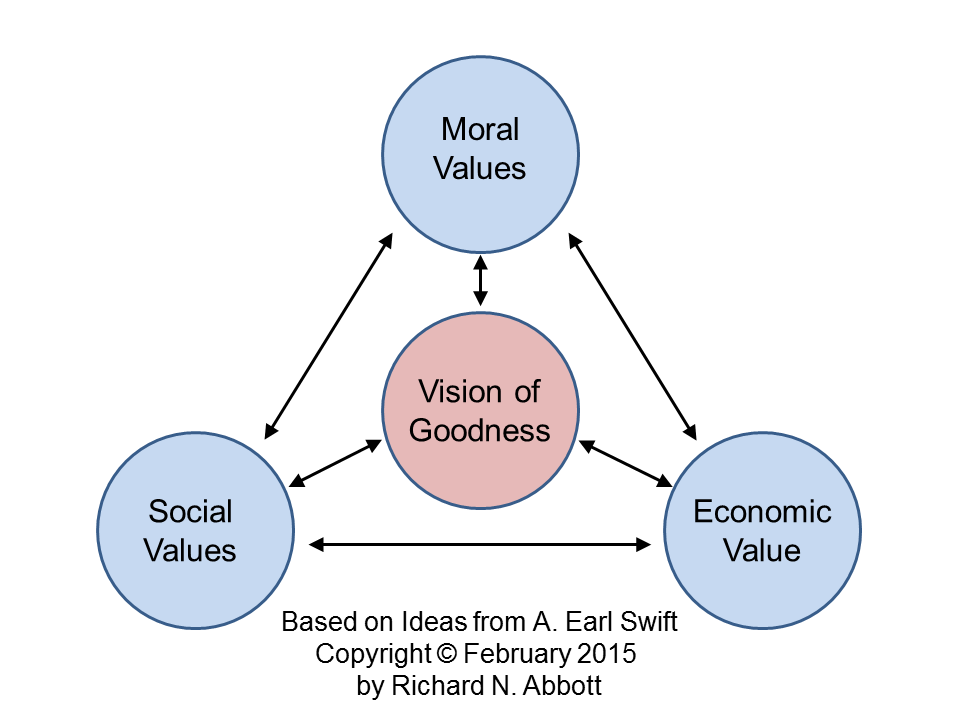

Three Kinds of Values. Because of the importance of values in the complex, decentralized decision-making processes of modern organizations and societies, success usually requires decision-makers to place values at the center of organizational life. The basic kinds of values a company, a church, or a non-profit organization must consider come in three forms: economic, social, and moral.

When we look at values from an economic perspective, we are usually talking about the usefulness of some good or service for an individual or a group. This results from a combination of the importance of the goal to be achieved and the “utility” or “fitness” of the good or service in achieving that goal. Economic value is usually expressed as a price, but it can also be expressed as a non-monetary worth determined through the reciprocal exchange of benefits.

Economic value is clearly central to business enterprises. Companies often talk about building stakeholder value or stockholder value as one of their key goals, and sometimes they even make it part of the corporate mission. It is important to realize, however, that all economic value has an ethical foundation based upon reciprocity, and without a just system of individual rights and responsibilities, economic value can be greatly diminished.

At the same time, long-term success depends on more than profitable economic exchanges. Earl knew that building economic value was critical to any business enterprise – a fact that was so obvious that it usually didn’t need to be mentioned – but he also believed businesses that survived and prospered over the long run had a purpose that transcended value defined merely in monetary terms. Toward the end of one of his articles on organizational relationships, he said: [17]

“Business has never been about making money. It is about meeting human needs. Making money is a necessary component of survival, but it can never provide the real reason for existence. We all have to breathe to live, but we don’t live just to breathe.”

This transcendent reason for existence was to be found in the social and moral values that guided corporate decision-making and in the integration of those values with the organization’s overall purpose and mission.

When we move beyond economic value and begin to consider values in a social context, we think about value in an entirely different way – as a kind of social norm. A social value is an internalized rule for appropriate behavior handed down to us from role models, something that promotes successful interpersonal interactions among members of a team, a group, or even a society. These social norms are culturally relative and vary from group to group, but within the group, they exert a strong ethical influence. A group might say about one of its norms, “There’s the right way, the wrong way, and our way.” A social value isn’t about absolute right and wrong, as if there is no other legitimate manner in which a person could behave; instead, it’s about conforming to group standards in order to maintain the group’s internal harmony and cohesiveness and to better define its unique character relative to other groups.

In contrast, when we talk about values from an moral perspective, we focus on the universal ethical principles that are intended to apply to everyone, everywhere, all the time, whether they are a member of the group or not. Values, used in this sense, are integrating ideals or moral absolutes that give meaning to an organization’s, or an individual’s, vision and purpose, but because they are absolutes, they do not define an organization’s distinctive personality.

Conforming to basic moral values is the first threshold an organization must clear in order to remain viable over the long run. There are some principles that are necessary for sustained cooperation in essentially any situation. No group could stay together very long if murder was the preferred way of solving internal disputes, if lying was generally considered morally superior to telling the truth, or if stealing was held in higher esteem than honest work. All sustained group cooperation depends upon mutual trust. Some behaviors build trust and other behaviors destroy trust. This is a fact of life, and it is the reason the human species shares a general set of common morals.

Finally, when we think about the shared values that form the center of our common life together, we are talking about an integrated balance of all three kinds of value – economic, social, and moral. These values are integrated together in a holistic vision of what goodness is. Aristotle talked about this over 2,300 years ago when he called goodness the target at which all things aim: [18]

“Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and pursuit, is thought to aim at some good; and for this reason the good has rightly been declared to be that at which all things aim.”

Put simply, every action we take aims at some goal, and that goal aims at another goal, which in turn aims at another until we come to the ultimate goal, which is our vision of what goodness is.

As an example, Aristotle said the purpose of making a bridle is to equip a horse. Among several alternatives, the purpose of equipping a horse might be to ride into battle. We might say that the purpose of riding into battle would be to achieve a military victory, and the purpose of military victory would be to subdue the enemies of freedom and justice. Subduing the enemies of freedom and justice should lead to a better world, which in turn leads to the ultimate goal – what Aristotle called “the chief good.” Everything is connected to everything else through a similar chain of purposes. We drive to the doctor to get a checkup; we get a checkup to maintain our health; we maintain our health so that we can serve others; we serve others to promote a better world; and we promote a better world in order to achieve our vision of what ultimate goodness is – in other words, “the chief good.” Through these chains of purposes, we develop an integrated vision of a better future, and this integrated vision makes us more successful by preventing us from working at cross purposes with ourselves. This integrated balance of economic, social, and moral values therefore becomes an effective foundation for success for an individual, a group, or even a civilization.

Conclusion. I am not sure Earl would have agreed with everything I have said in this initial blog. I wish he were here to give me his opinion. I do know that most of the ideas I presented in this article were inspired by what I learned from him through the years, and that is why my first blog entry was devoted to his ideas.

In subsequent postings, I will be talking about how these ideas combine with the insights of other people to form the foundation of a comprehensive worldview. This blog will ultimately be an exploration of a potential global paradigm. There is lots of ground to be covered. Because it is an exploration, I may change some of my opinions as I travel over the intellectual landscape, and I hope to be aided in my explorations by the insightful comments of others who are thinking on similar topics.

What will remain constant is an unwavering focus on the three unchanging principles of change. It may not be obvious, but I have been talking about these three principles throughout this introductory discussion. Earl’s three types of decision making ultimately translate into the three basic drives of human nature – individual freedom (leading to variation and diversity between people), group consensus (leading to selective rules for belonging and group cooperation), and authoritative purpose (leading to growth and progress). From a larger perspective, these drives translate into three basic principles of evolution – random variation, natural selection, and growth. These are the three unchanging principles of change that have governed everything from the evolution of the cosmos, to the evolution of life, to the development of human societies. I will have much more to say on each of these principles in later postings.

=======================

Papers and Speeches by A. Earl Swift:

December 11, 2004 – Speech Presented by A. Earl Swift at Pepperdine University

A commencement address to the graduates of the Graziadio School of Business and Management of Pepperdine University, Saturday, December 11, 2004.

A. Earl Swift, “The Integration of Organizational Relationships: The Role of Authority in the Global Economic Order,” World Energy Magazine, v.6, n.3, August 7, 2003. (Also see PDF version.)

“The Interdependence of Organizational Relationships: Leadership in the New World Order,” World Energy Magazine, v.5, n.3, October 23, 2002. (Also see PDF version.)

“The Evolution of Organizational Relationships: Multicultural Ethics and the New World Order,” World Energy Magazine, v.5, n.2, August 20, 2002. (Also see PDF version.)

“The Dynamics of Organizational Relationships,” World Energy Magazine, v.5, n.1, October 23, 2002. (Also see PDF version.)

A Tribute to A. Earl Swift:

A. Earl Swift: Founder of Swift Energy Company, originally published in Swift Energy Company’s 2006 Annual Report

=======================

References:

[1] Swift, A. Earl, “The Dynamics of Organizational Relationships,” World Energy Magazine, v. 5, n. 1, Houston, TX, April 18, 2002, pp. 48-54.

[2] Swift, A. Earl, “The Dynamics of Organizational Relationships,” World Energy Magazine, v. 5, n. 1, Houston, TX, April 18, 2002, p. 54.

[3] For more on win-win transactions, see: Covey, Stephen R., The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change, New York: Simon and Shuster, 2004, pp. 215-246.

[4] Robert L. Trivers proposed in the early 1970s that reciprocity played a key role in the evolution of cooperation between unrelated individuals. One individual will help another in the expectation of future reciprocation. See: Trivers, Robert L., “The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism,” The Quarterly Review of Biology, Vol. 46, No. 1, The University of Chicago Press, March 1971 pp.35-57.

[5] Reciprocity can also entail more complicated strategies. One individual may help another in order to obtain help from a third party or to boost his or her reputation in order to obtain the help of others at a later date. See: Nowak, Martin A., “Five Rules for the Evolution of Cooperation”, Science, vol. 314, no. 5805, December 8, 2006, pp. 1560-1563.

[6] In the early 1980s, the political scientist, Robert Axelrod used game theory and computer modeling to show how reciprocity could have led to the evolution of cooperation between unrelated individuals. He held a contest between social science researchers to show what competitive strategy would lead to the best competitive success. A simple strategy of reciprocity called “Tit for Tat” won the contest. See: Axelrod, R. and W. D. Hamilton, “The Evolution of Cooperation,” Science, Vol. 211, No. 4489, March 1981, pp. 1390-1396. Also see: Axelrod, Robert, The Evolution of Cooperation: Revised Edition, New York: Basic Books, 1984 and 2006.

[7] Swift, A. Earl, unpublished manuscript, The Common Thread, Chapter 3, p. 23.

[8] Swift, A. Earl, unpublished manuscript, The Common Thread, Chapter 3, p. 25.

[9] William D. Hamilton proposed in the 1960s that kinship was an important component in the evolution of cooperation. By helping a genetically related individual, an organism can increase the probability that its own genes will be passed on to subsequent generations. See: Hamilton, W. D., “The Genetical Evolution of Social Behavior, I,” Journal of Theoretical Biology, Volume 7, Issue 1, July 1964, pp. 1-16, and “The Genetical Evolution of Social Behavior, II,” Journal of Theoretical Biology, Volume 7, Issue 1, July 1964, pp. 17-52.

[10] Swift, A. Earl, unpublished manuscript, The Common Thread, Chapter 3, p. 28.

[11] The “Tit for Tat” strategy that was so successful in game theory begins with a predisposition to cooperate. In humans, this predisposition may be innate. Through socialization, this innate predisposition is developed into moral values as a person matures. See: Warneken, Fleix, and Michael Tomasello, “The Roots of Human Altruism,” 100, British Journal of Psychology, The British Psychological Society, 2009, pp.455-471.

[12] Leviticus 19:18 and Matthew 22: 36-40, Holy Bible, New International Version, Biblica Inc, 2011. [Downloaded from Bible Gateway.]

[13] This idea goes back to the code of Hammurabi, Mesopotamian king who ruled the Babylonian Empire from 1792-50 B.C.E. The idea also appears in the Bible. See: Exodus 21:24, Leviticus 24:20, Deuteronomy 19:21, and Matthew 5:38, Holy Bible, New International Version, Biblica Inc, 2011. [Downloaded from Bible Gateway.]

[14] Covey, Stephen R., The 8th Habit: From Effectiveness to Greatness, New York: Free Press, 2004, p.41.

[15] authority. Dictionary.com. Collins English Dictionary – Complete & Unabridged 10th Edition. HarperCollins Publishers. (accessed: February 23, 2015).

[16] Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483, (1954).

[17] “The Evolution of Organizational Relationships: Multicultural Ethics and the New World Order,” World Energy Magazine, v.5, n.2, August 20, 2002, p. 120.

[18] Aristotle, Nichomachean Ethics, Book 1, Part 1, 350 BCE.